Gaming isn't crashing: It's stagnating, but it's still going to be very painful.

On last year’s retrospective on game development, I predicted that the gaming industry layoffs wouldn’t stop this year. Sadly, I was right on the money: We’ve surpassed the amount of layoffs from 2023 back in June.

And it’s not just the big studios that are suffering. The indie industry is struggling with a completely different kind of situation.

The AAA corporate greed: Game development as slavery?

A bit of a flippant title, but it’s seems to be becoming ever increasingly truer with time in big studios with an economic model that’s based on the model of tech giants from the United States.

I’m not going to delve deep into US economics, but the gist of it is that it’s mostly growth driven: “The more reach you can obtain, the happier the investors become. We’ll see the actual earnings later.”

This is one of the reasons big publishing firms spend so much money on marketing: It’s one of the main drives for potential growth, which gives them a lot of leverage.

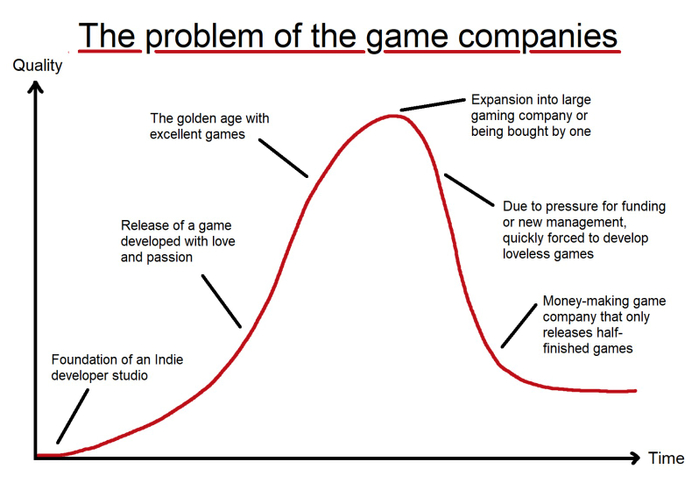

In their desire to achieve more growth, studios are pressured to hire more staff than they actually need, because having more jobs tends to look good on investors. This often results on a troubled situation in which management is found being incapable of coordinating a team of such size, which will probably have an impact on why the development won’t get anywhere. And once the project doesn’t seem to be delivering what it’s been promised, companies resort to cutting costs by axing jobs that they knew beforehand shouldn’t have hired in the first place, and attempt to “try to look good and responsible” by applying damage control to their best.

This is especially true in companies that go public in the stock market, as there is a constant pressure for exponential growth; since other companies are doing this, stockholders may consider that your company might be stagnating if the stock value doesn’t keep increasing, even if it’s being inflated. Game companies even resort to buying back stock just to do this.

And if that wasn’t enough, some publishers have also found an exploit: The early access rug pull. This really shady practice consists on releasing a game as an early access game, hoping to gain traction. But the game will be full price while in this phase. If the game eventually flops during development, since they’ve already gotten some earnings, they pull the rug, stop development altogether, and run away with the cash while at the same time leaving just a handful of programmers for fixing bugs only. This is fraud and punishable by law.

This is exactly what happened with Take-Two when they shut down Intercept Games, putting the final nail in the coffin of Kerbal Space Program 2’s troubled development. And last year we also had the Fntastic’s The Day Before incident.

And this is why now I don’t preorder games anymore, even if it comes with bonuses. Ever since downloadable patches became a thing, I’ve became very cynical for how a game is going to come out.

Although maybe I will consider preordering something I might want at all costs in a physical format and I think there won’t be many physical units in supply. It used to be the case with Metroid games, but nowadays the supply has been pretty hefty enough to make me wait for the release.

Indies and the lack of funding

This is something that has been happening more often than not in studios all over Europe, a region where most of the game throughput come from indie studios, which normally don’t have much capital to embark themselves onto making videogames.

Ever since the worldwide lockdown due to the pandemic period ended, things have gotten for the worse for indie studios. During the pandemic, investors were able to read the tea leaves and figure out that games were going to be extremely valuable during lockdown, from a convenient way to cope with having to stay indoors, to a collectible commodity. Roblox is the textbook example of this: It exploded in popularity during the 2020s, and went public at an astronomically high market value of over 7 times the value of Ubisoft, but fell victim to the 2022 bust and quickly devalued as restrictions went down.

The Web3 fiasco further exacerbated the damages, because it fostered a lot of interest on game projects that had blockchain-like features, but these were simply terrible investments that could be considered a downright scam. Their failure caused a lot of devaluation of a lot of startups, and many tech investors grew extremely wary of investing.

Tech bust of 2022 explained (3:05)

The shockwave of this effect is still in effect to this day.

However, game studios started with their massive layoffs a year after the bust because videogames are generally more of a long-term investment and it took some time to see that they weren’t as profitable anymore.

Investors in Europe face similar concerns, and are being now more conservative and risk aware because game European studios are increasingly being handled like tech companies from the United States.

And if that wasn’t enough, the tech industry did eventually find something that seemed promising: Generative “AI”, a field in which videogame development seems to have have yet to find anything to take advantage of —let alone that its usage is deemed unethical within the industry— and with nothing else seemingly equally promising in tech, investors have flocked in herds to those greener pastures.

We’ll see how that “AI” biz goes in the next few 5 years or so.

Crowdfunding isn’t what it used to be 10 years ago, and it has become very stagnant with no hopes of improving. Early access used to provide a lot more confidence that a game would eventually be completed, but also the increased awareness of scam-like or development going wrong has made people very wary of putting their own money on a game. And if your game failed to meet expectations, it’s game over; your now forever ruined public image would seriously affect sales of future projects you would be involved in.

Hardware development from now might be having diminishing returns

Do you feel like something is happening to next-gen games as of lately? Like, despite the technological advances of the latest in console gaming hardware, the games themselves are failing to live up to their expectations? Like it’s all ports of the previous generation? If you’ve answered “yes” to any of the questions above, you’re not alone.

I think there’s now enough room to start worrying about the fact that gaming hardware has become “too powerful”. Moore’s law applies to hardware, not software. And it is my belief that we’ve reached the point where despite computers are becoming increasingly more powerful, it is no longer possible to come within grasping distance to the limit on what consoles are capable of. At least, not unless you have humongous resources and even still resort to unethical development environments.

However, expectations of players increase with each new generation of hardware. And unfortunately, their expectations have reached a hard glass ceiling with this current generation.

On that metric, the PlayStation 4 and Xbox One lie very close to the line of diminishing returns. I would personally not go beyond this.

But even still! This is precisely where I see a ray of hope within the darkness.

Konnichiwa, baby! Japan is back!

The Eastern game industry hasn’t been affected as much in this wave of decline, because their economics work in a more conservative way than those from tech in the United States.

Take a look at Nintendo, for example. Instead of laying off employees, they resorted to actually increasing their salaries by 10%. Japanese —and I think Korean companies as well— tend to operate very differently than those from the United States, and to a lesser extent European companies. Instead of valuing growth over anything else, they value resilience and a long-term but sustained growth, and one of the key factors for that resilience is workforce.

Whether it’s a sociocultural or a business managing aspect, it’s a fact that in Japan, workers are a vital part of any company, people consider the workplace “their second home”, and the actual legal action of firing people is massively restricted. This drives companies and game studios alike to keep the workers that they have, even at a loss.

It’s worth noting, however, that Japanese companies do mass hiring of people, but these are usually students scheduled to graduate in spring in order to replace their oldest, retiring workers.

Due to the aging of Japanese population, young workers have become so valuable that most Japanese companies will primarily or almost exclusively hire people from the pile of new graduates, and compete very hard to recruit the most academically successful candidates.

Unfortunately this has the very nasty effect that once your “freshly graduate card” expires, you are incredibly less likely to find a job, which adds a lot to the importance of keeping your employees. Some black companies excuse their practices by reminding their workers that they probably won’t find a job anywhere else, too.

Because of the social problems that this century-old custom has brought (and especially after its mass use after the post-war Japanese economic miracle), the Japan Business Federation, with some of the largest companies in the country, said that they are “no longer required to practice this custom” in 2020.

But this isn’t an order nor law. Do you really think they’re gonna stop?

Instead of panicking and minimizing losses by panicking with damage controls, Japanese companies will generally accept the fact that hard times are coming, and prepare themselves in order to “at least not make it that hard” to be able to get up and kick off when times get better. This hardening-based culture generally makes companies less prone to collapsing, and instead have simply a flatter overall productivity.

Japanese studios also have it much easier to secure funding than studios in Western countries because they have other ways to get funding that aren’t as prominent in the West.

Method 1: Trans-media projects and the production committee

A very large amount of games are actually trans-media projects handled by a production committee. This method of funding is also fairly common in Europe, but Japanese production committees tend to treat projects from the same IP equally, and get a more fair share of funds than with an European “main project and accompanying projects” model. In anime circles, production committees are seen rather controversial, but it’s still a major source of funding for many entertainment and merchandising industries alike.

While games aren’t a common sight in these committees, if a game publisher does become part of one, it would allow the studio working on the game to get piggybacked by this system, and not only get easy funding, but also obtain protections against losses should the project fail commercially, even if it means a more equal share of profits with the rest of projects —again, Japanese companies focusing on resilience rather than growth. Game studios themselves joining are way less common since they generally don’t have the capital to make a contribution in the committee.

In Europe, games aren’t usually the main project and the overall trans-media project tends to have a more limited funding and reach, so they typically tend to be of smaller scope and of less quality than Japanese ones.

Method 2: Licensed games and publishers

Other projects are usually licensed games commissioned by a publisher.

Licensed games were particularly notable in the United States industry until the 2000s, but publishers would outsource games for as many platforms as possible to other developers with minimal funding and tight deadlines, baking on the fact that brand recognition alone would sell the game. But this resulted in a huge amount of terrible quality games and their eventual demise in the 2010s, as game development became costlier and consumers became more informed on the industry as a whole.

Extra Credits on licensed games in the United States (8:09)

Also known as shovelware. It also explains their eventual downfall on PC and home consoles.

Japanese publishers, on the other hand, act in a similar way to Spanish licensed game publishers during its silver age with mobile games in the 2000s: Focusing on a single game and platform (or leveraging cross-platform if possible) and having a more respectful budget. Japanese developers also earn their trust with publishers through these commissions, allowing them to secure funding on their projects based on the developers’ own IPs.

It’s worth noting that this has nothing to do with where the original IP comes from, but rather where the publisher is based. Capcom —a Japanese company and publisher— has published many Disney titles that were significantly better in quality than other Disney licensed games.

Method 3: Self-funding

Smaller and indie studios are also capable of funding their own projects because they tend to focus on games that are much smaller in technical scope: Visual novels. This allows them to make games with much less funding, while remaining somewhat able to generate a small profit.

However, not every visual novel developer seeks that: A particular category of games, “doujin software”, involves games that are based on existing IPs and made as a hobby rather than for profit. Most of these projects are made at a loss, but thanks to the strong market of fan-based projects, developers may expect to grow up to be successful later on.

While visual novels aren’t as notorious as they did in the early 2000s, they still account for a significant portion of the Japanese game market, and thanks to opening up to English and Chinese speaking markets, the visual novel industry is still holding on strong.

The dawn of new hardware

A promising prospect is that the Japanese economy seems to have been rebounding since the past couple of years (although the Bank of Japan did make a cautionary warning for trade markets due to unstable foreign markets) so it’s possible that the Japanese game industry could boost itself up again despite the hardships.

Unfortunately I don’t know about the Chinese and Korean game industries enough to provide more information about them, but it does seem like they may be going through good times as well.

For now, it all comes down to Nintendo’s next console. One of the reasons why I have bet for a powerful home console as Nintendo Switch’s successor (and short-time companion) is partly because Nintendo needs to compete with Microsoft and Sony with their Xbox Series and PlayStation 5, and the economy of Japan seems to be at a very adequate time to strike hard with a powerful system.

But this is absolutely not what I want! This would place the bar for AAA games above the diminishing returns point, and both AAA and even AA studios would feel pressured to scale up their scope in projects to meet up with hype and expectations. In other words — this spells an unsustainable hell.

Rather, I’d prefer Nintendo to go another route, and actually release a Switch 2, and be something comparable to a PlayStation 4 Pro or an Xbox One. This would make them leave the overly engineered home console market and dive deep into the affordable hybrids market such as the Steam Deck and Asus ROG Ally. I wouldn’t ask for more. The fact that they plan to flood the market with the gaming system in order to fight with scalpers makes me think a little bit that they could be taking this strategy, but as I discussed in a previous post, there are several reasons that make me think otherwise…